- See more: INTERVIEWS

- Tags: Interviews in English

Sometimes the old is fresher than the self-consiously new.

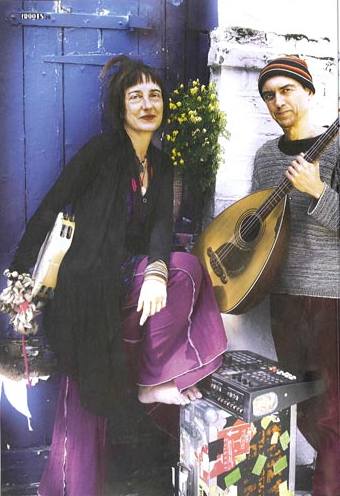

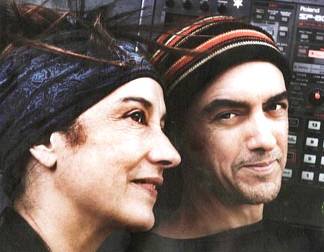

“We were one of the very first bands that dared include a traditional song in their album to not have stones thrown at us for this”. Kristi Stassinopoulou and Stathis Kalyviotis, No 1 for months on the World Music Charts Europe with their new Riverboat album Greekadelia, are in my kitchen remembering the time when it started to become less physically hazardous to play folk music in Greece. It’s not that the music was bad, but that traditional songs were used by the junta to stoke up nationalistic fervour, presumambly inviting stone throwing by those of a leftish presuasion. But if the music contained modern elements, perhaps involving electricity,then the stone chucking would also hail from those on the right. Either way, it didn’t look good for musicians.

Stassinopoulou and Kalyviotis were shining lights in a movement afoot in the early ’90s to reclaim folk music for the young, for hte left. Although they had met at the fag-end of hte ’80s, this time really marked the start of her and Kalyviotis’ missile free, folk-rooted and prodigious musical collaboration.

And now Greekadelia comes stuffed full of gems of Greek traditional songs performed in a the couple’s immitable style. It marks a change for them, not just because the recordings are not of their own compositions; they are the result of the pair working together as a duo and a move away from the bigger band sound that has typified their output for many years.

It was a change in part inspired by their appearance at London’s Roundhouse for fRoots’ 30th birthday bash. Busy recording a new album around that time, the pair were bringing in all the friends and musicians they normally worked with, but with a mounting sense of unease. it was sounding all too familiar. “No, we are tired of this,” they said. “In our free time,” Stassinopoulou tells me, we just play folk songs. Stathis practices the lute by playing old folk songs, and I practice the bendir by playing along with recordings of the old tunes. That’s our musical practice but also our joy. We also do it on the beach or when we go camping; we have the lute and the bendir.”

True to form, they had instruments with them on a trip to London which coincided with the fRoots party, and agreed to do an impromptu guest spot when invited. “We did one song, but were very, very uncertain that we should do this in the middle of these huge bands that were performing in this huge place wherre we had never been before. We said OK, let’s do it for Ian because he’s a friend, and when we did, everybody said, ‘Ah, that’s so nice. Why don’t you record something like this?’”

And so, on returning to Greece, they both threw themselves into extensive research, unearthing songs from the rural areas of the Greek mainland and its islands. The prodigious archive of enthomusicologist and folk singer Domna Samiou proved a valuable source of information and Stassinopoulou acknowleges that without her work, many songs would have been lost. A student of the conservative musicologist and Byzantine music scholar Simon Karas, Samiou (wose death this year aged 82 sparked national mourning) was hugely influential in Greece as a singer and teacher, working tirelessly like Karas to preserve the old traditions.

Her thorough conservatism, though not as strickt as her mentor’s was softened through her work with the man generally referred to as ‘the Greek Dylan’, singer-songwriter Dionysis Savvopoulos. Inspired by Fairport Convention and of course Dylan himself, Dionysis was the first Greek musician “to combine a rock band with traditional instruments and traditional rhythms”. Inviting Samiou to sing with him, he introduced her to the burgeoning underground alternative audience emerging through the Athens club scene in the mid ’70s, directly after the fall of the junta. This began to popularise traditional music amongst the left-inclined young, starting the long slog of wrenching the music away from its purely right-wing associations.

Sadly this proved a false dawn for an attempt on the music’s de-politicisation as the movement was suppressed immediately, not to re-emerge for another 20 years – at the time when Kalyviotis and Stassinopoulou happily discovered that playing traditional music was not an excuse for a stoning.

When musicians turn to the traditional songs of their homeland, as these two are doing, it’s easy to assume their musical activities are fuelled by looking back in search of their roots. Kalyviotis is having none of it.

“Speaking for myself it was never ‘back to’ anything. I grew up with the music of the city, with rock, with funk. For me ‘traditional’ was something that I discovered in my 20s. Nobody in my circle knew about it. It was something new. It wasn’t a need to ‘go back’ to anything. I remember I was about 15 years old and I was listening to punk music in the year 1980. I have an uncle who is from Pontus and we went to his house and he put on music from Pontus. It had a very strong beat. I heard it and I said ‘Oh my god, this is punk rock!’ So for me it was new. Anyway I don’t like to speak about the past, all things like this. I don’t like it.”

Stassinopoulou also grew up with rock and funk and the music of the city: like Kalyviotis she was brought up in Athens. Before forming the ‘garage rock’-inspired band Selana with him, she enjoyed an illustrious stint as Mary Magdalene in the original Greek production of Jesus Christ Superstar in the late ’70s, and in 1983 was the Greek candidate in the Eurovision Song Contest. A stretch in Evita followed. (Her earlier story, in a 2003 interview from fR237, can be found on the fRoots web site.)

Unlike their personal relationship, Selana was fairly short-lived as Kalyviotis and Stassinopoulou decided to work together on her solo albums, typically featuring his musical arrangements set to her lyrics, and down the years various combinations of musical friends and collaborators forming her band.

For Stassinopoulou the relationship with traditional music is not so clear-cut as her partner’s. “For me,” she says, valiantly drinking the coffee I’ve made, “although I grew up in the city there are memories of these songs apart from just rediscovering them. I was not into them, but I had the memories of the songs.”

As a child she would spend time with her parents in her father’s native Pelopponese and remembers singing the more famous folk songs on the car journey taking them there. Her parents were not unenthusiastic members of the church and services there inspired Stassinopoulou’s love of the Byzantine music that Karas documented so thoroughly. She explains that he was the first to say that Greek folk music of the rural areas is a direct extension of Byzantine church music. Now, she says, course it’s the same music. It’s not that it derived from the church. It’s the church who took the ancient existing scales and the modes, maqams like they say in Arabic or ragas as they say in India or troparia in Byzantine, and they used them in church so as to make the church music popular and get people to turn to religion. I’m talking about the scales, rather than the traditional rhythms because there was no rhythm in Byzantine music.”

Perhaps this was down to the fact that the rhythms in traditional folk music are hard-wired for dancing. Kalyviotis believes that “It’s something you have to be Greek to feel, because first of all, the rhythms are not the usual rhythms that you have in Western music that use a four, most of the songs are 7/8 or 9/8 or 5/8, which for us it was very easy because it’s…” “It’s like our DNA,” Stassinopoulou interjects. “For me the 7/8 is like DNA.”

A multi-cultural DNA, as she says: “One very important aspect of Greece is that we are situated between the borders of three continents. Greece is not Europe only, it’s not Asia only, it’s not Africa only it’s all of these. And this is the big virtue of the music and the culture, and also the big problem sometimes because we have to find an identity and decide. I don’t think that people should decide where they belong: this is a little bit black and white, which I never liked in my life. But the thing is that we are in between these cultures and therefore so is the music.”

“You have a lot of different styles and rhythms and scales that pre-date Byzantine times, even the writing of the notes in Byzantine music goes back to two or three specific inscriptions of hymns for the god Apollo, using the same scales and notation.”

The history of movement, people, ideas and cultures embedded in their musical discoveries inspires both Kalyviotis and Stassinopoulou. As does the idea that folk dance brings people together, whatever their personal beliefs. Dancing around to an iPod, she says “can no way be compared with the experience of dancing when people are holding their hands and they are in a circle, and suddenly there is one breath coming out of all this circle, one speed, one meditative kind of union and physical body type of connection. Every Wednesday evening people that we don’t know come from all areas of Athens and we have this dance. Suddenly you hold the hand of someone who may be something very hostile to you or something very, very, different from what you are. This you only discover when you’ve finished. Suddenly you find out, oh my god, I have nothing to do with these people. Or, with this guy, yes he has the same beliefs, as me, the same attitude of life. It makes no difference while you dance. You are connected. You are one with all of them. It is a kind of being on the earth feeling, to be able to connect yourself with all the alternatives.”

Presumably this feeling was why the Colonels found that tying traditional music and dance to their cause was so useful. But for Stassinopoulou, discovering that she was moved in the same way by folk, church music and the songs of the Velvet Underground, the political associations grated. They formed barriers that she wants to see abolished.

Yet she is not naive about the implications of traditional music, pointing to one reason as to why it’s been a source of shame. She tells me about Kato Sta Dasia Platania, sometimes known as Diamandoula: “I feel this song was hidden because it’s speaking of a strange story that must have happened in the rural areas in the village areas last century. There was a rape of a girl. It’s very sad. Talking about the past and all these things is not always positive. The nature of Greek life in the rural areas has been very tough and very conservative and very bad.”

Kato Sta Dasia Platania features on Greekadelia with other rare songs from specific places. The not so rare also get a look in. Halassia Mou popularised in the ’50s is now so famous, says Stassinopoulou, that it can no longer be considered local. But whatever their provenance, all the songs on the album benefit not just from Kalyviotis’s multi-instrumental virtuosity but his brilliance with new technology.

Using tape loops and found sound, he captures the atmosphere of the songs and the sounds of the traditional instruments. He eschews the depressingly popular use of electric guitars to mimic clarinet solos which only ever makes the songs louder and kitsch (though not in a good way). Both Kalyviotis and Stassinopoulou, whilst keen to show respect for the songs, are not of the view that it’s particularly useful to try and perform the music in the way that it was played centuries ago: pointless, in fact, thinks Stassinopoulou, given that no-one now can really know how it was played then anyway.

But whilst the music is given a modern twist, the poetry of the old lyrics is as moving and relevant today as when it was written. The writing style attracts Kalyviotis, he says, because it’s a poetry that only people that are close to nature can display. For Stassinopoulou it brings back childhood emotion.

“Neratzoula, whenever I listened to it it used to be very famous Greek song I would cry. It’s the Words of it combined with the melody. Neratzoula is a nickname and it means the bitter orange tree, but it’s also a female name so, ‘Neratzoula full of leaves, where did your flowers go? Where did your beauty go?’ and Neratzoula is answering ‘the North Wind blew and took it all away.’p>

The songs transport her back to favourite scenes, such as tiny white chapels seen from the sea, dotting the islands as they perch in the cliffs. For her, the words are returning to natural things, taking care of what nature is telling you. They bring me close to something that is getting lost, something unique.” And she is notjust talking personally.

“It seems to me,” remarks Kalyviotis “that at least one of the songs, Me Galsan Ta Poulia The Birds, They Fooled Me, reflects what’s happening now in Greece. It says that the birds they fooled me, they said I’d never die. Sol build a big house and from one of the windows I see all the valley, and from there I see Death coming. So for me it’s a representation of all that is happening now in Greece, and maybe the next step in what we are calling development of the western world

Life in Athens now, they tell me, “is indeed very rocky, very heavy, the last years like a dark, black cloud and it’s difficult to get to the truth of what’s going on.” The depression and anger and feeling of no-hope swirling around them have sharpened their focus on music. They want to spread a little joy. Although the recent gig season was one of the poorest they’ve ever endured, one of the good things to come out of the crisis, they say, is the work that musicians are now producing.

“Until now, many good musicians were playing with big names in big commercial clubs which nowadays have serious problems,” says Kalyviotis. “It’s where the big money went, so they are out of work and this has led to the creation of new groups and they have started again to play clubs. And I believe that this will create something good.”

“Just to describe a little better what he’s saying,” interjects his partner, “if you would tell someone in the street ‘I am a musician,’ he would say ‘Where? In which club?’ And if you say ‘Not in these, in the others,’ nobody even knew the ones that we have been playing. They were more specifically for young and for alternative people. Now there is a return to them because all these big places are collapsing economically. You have good musicians that, in order to make a living, were obliged to go and work there, playing something like Turbo-Folk. Now you have them making different kinds of music and being able to dedicate themselves to smaller groups etc. This is what you were saying, Stathis? I don’t want to interfere, just to make it clear…” She pauses. “Though even these small clubs, it’s hard to have a real audience like we used to have some years ago. They were small clubs, but filled with people. Now if you have 30 or 40 people in a small club it’s considered a big success. Everybody’s trying to minimise the ticket prices etc because people have no money;, sometimes we’re paid just ten Euros.”

Stassinopoulou and Kalyviotis are still in a minority of musicians who sing in Greek. Whilst there are schools nowr which specialise in Greek traditional music, the majority of young musicians there want to learn jazz or sing in rock and pop bands in English. it’s a hangover from the ’60s and ’70s, when that music underground in Greece held connotations of openness and free love and for a long time was banned on Greek radio, ramping up its attractiveness. It’s a source of frustration for Stassinopoulou. “Among the kids of our friends, the mainstream music they listen to which is considered very alternative is imported music only, music which is with an electric guitar, with drums and bass or even more modern and more interesting types of music like hip hop. Things that have not been born in our country. The main thing for me is the language. I mean you cannot be singing about your love affair and writing lyrics about your beloved and express yourself in English (it you are not). It’s impossible. You’re just a monkey.”

Stassinopoulou and Kalyviotis though, have still managed to build up a solid, sizeable and dedicated young audience in Greece through the years, and now to their delight they are gaining older fans previously deterred by their ‘alternative’ reputation. After giving a demo of Greekadelia to their friend Yannis, he called to say his mother had heard it. “She came to me crying: ‘these are the songs that I was singing in my village. I am so moved to hear this. What is this? You Iisten to the same songs that I grew up with?’ And he replied ‘Yes, it’s my friends. It’s Kristi and Stathis.’ ‘Oh,’ said his mum, ‘Tell them congratulations. This is so nice what they are doing.”

For Stassinopoulou and Kalyviotis, this “was the most moving thing. it was the thing that made us say ‘OK let’s go on with this,’ because we were wondering whether we should or shouldn’t go on with this album.” Funnily enough they experienced similar doubt when working on their other World Music Chart Europe N0 1 album, 2002′s The Secrets Of The Rocks. For that particular release seeing the light of day we have to thank their farsighted friend and early manager Thalia lakovidou, who sadly died in 2004.

Now for their latest album we should be grateful to Yannis’s mum who also told him: “They’re doing what they should be doing to make young people go back to these songs.” It’s what Stassinopouiou and Kalyviotis are aiming for. And if their modern take on the old songs can show people that singing in their own language does not necessarily indicate rabid right-wing conservatism, then Greekadelia is really a freedom cry for Greek folk music. And it makes you dance!

Elisabeth Kinder